Major histocompatibility complex

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a large genomic region or gene family found in most vertebrates that encodes MHC molecules. MHC molecules play an important role in the immune system and autoimmunity.

Proteins are continually synthesized in the cell. These include normal proteins (self) and microbial invaders (nonself). A MHC molecule inside the cell takes a fragment of those proteins and displays it on the cell surface. (The protein fragment is sometimes compared to a hot dog, and the MHC protein to the bun.[1]) When the MHC-protein complex is displayed on the surface of the cell, it can be presented to a nearby immune cell, usually a T cell or natural killer (NK) cell. If the immune cell recognizes the protein as nonself, it can kill the infected cell, and other infected cells displaying the same protein.[2]

Because MHC genes must defend against a great diversity of microbes in the environment, with a great diversity of proteins, the MHC genes themselves must be diverse. The MHC is the most gene-dense region of the mammalian genome. MHC genes vary greatly from individual to individual, that is, MHC alleles have polymorphisms (diversity). This polymorphism is adaptive in evolution because it increases the likelihood that at least some individuals of a population will survive an epidemic.[2]

There are two general classes of MHC molecules: Class I and Class II. Class I MHC molecules are found on almost all cells and present proteins to cytotoxic T cells. Class II MHC molecules are found on certain immune cells themselves, chiefly macrophages and B cells, also known as antigen-presenting cells (APCs). These APCs ingest microbes, destroy them, and digest them into fragments. The Class II MHC molecules on the APCs present the fragments to helper T cells, which stimulate an immune reaction from other cells.[2]

Contents |

Classification

In humans, the 3.6-Mb (3 600 000 base pairs) MHC region on chromosome 6 contains 140 genes between flanking genetic markers MOG and COL11A2.[3] About half have known immune functions (see human leukocyte antigen). The same markers in the marsupial Monodelphis domestica (gray short-tailed opossum) span 3.95 Mb and contain 114 genes, 87 shared with humans.[4]

Subgroups

The MHC region is divided into three subgroups, class I, class II, and class III.

| Name | Function | Expression |

| MHC class I | Encodes non-identical pairs (heterodimers) of peptide-binding proteins, as well as antigen-processing molecules such as TAP and Tapasin. | All nucleated cells. MHC class I proteins contain an α chain & β2-micro-globulin(not part of the MHC encoded by chromosome 15). They present antigen fragments to cytotoxic T-cells via the CD8 receptor on the cytotoxic T-cells and also bind inhibitory receptors on NK cells. |

| MHC class II | Encodes heterodimeric peptide-binding proteins and proteins that modulate antigen loading onto MHC class II proteins in the lysosomal compartment such as MHC II DM, MHC II DQ, MHC II DR, and MHC II DP. | On most immune system cells, specifically on antigen-presenting cells. MHC class II proteins contain α & β chains and they present antigen fragments to T-helper cells by binding to the CD4 receptor on the T-helper cells. |

| MHC class III region | Encodes for other immune components, such as complement components (e.g., C2, C4, factor B) and some that encode cytokines (e.g., TNF-α) and also hsp. | Variable (see below). |

Class III has a function very different from that of class I and class II, but, since it has a locus between the other two (on chromosome 6 in humans), they are frequently discussed together.

Responses

The MHC proteins act as "signposts" that serve to alert the immune system if foreign material is present inside a cell. They achieve this by displaying fragmented pieces of antigens on the host cell's surface. These antigens may be self or nonself. If they are nonself, there are two ways by which the foreign protein can be processed and recognized as being "nonself".

- Phagocytic cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, and monocytes degrade foreign particles that are engulfed during a process known as phagocytosis. Degraded particles are then presented on MHC Class II molecules.[5]

- On the other hand, if a host cell was infected by a bacterium or virus, or was cancerous, it may have displayed the antigens on its surface with a Class I MHC molecule. In particular, cancerous cells and cells infected by a virus have a tendency to display unusual, nonself antigens on their surface. These nonself antigens, regardless of which type of MHC molecule they are displayed on, will initiate the specific immunity of the host's body.

Cells constantly process endogenous proteins and present them within the context of MHC I. Immune effector cells are trained not to react to self peptides within MHC, and as such are able to recognize when foreign peptides are being presented during an infection/cancer.

HLA genes

The best-known genes in the MHC region are the subset that encodes antigen-presenting proteins on the cell surface. In humans, these genes are referred to as human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes; however people often use the abbreviation MHC to refer to HLA gene products. To clarify the usage, some of the biomedical literature uses HLA to refer specifically to the HLA protein molecules and reserves MHC for the region of the genome that encodes for this molecule. This convention is not consistently adhered to, however.

The most intensely studied HLA genes are the nine so-called classical MHC genes: HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DPA1, HLA-DPB1, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DRA, and HLA-DRB1. In humans, the MHC is divided into three regions: Class I, II, and III. The A, B, C, E, F, and G genes belong to MHC class I, whereas the six D genes belong to class II.

MHC genes are expressed in codominant fashion[6]. This means that the alleles (variants) inherited from both progenitors are expressed in equivalent way:

- As there are 3 Class-I genes, named in humans HLA-A, HLA-B y HLA-C, and as each person inherits a set of genes from each progenitor, that means that any cell in an individual can express 6 different types of MHC-I molecules (see figure).

- In the Class-II locus, each person inherits a couple of genes HLA-DP (DPA1 and DPA2, which encode α and β chains), a couple of genes HLA-DQ (DQA1 and DQA2, for α and β chains), one gene HLA-DRα (DRA1) and one or two genes HLA-DRβ (DRB1 and DRB3, -4 o -5). That means that one heterozygous individual can inherit 6 or 8 Class-II alleles, three or four from each progenitor.

The set of alleles which is present in each chromosome is called MHC haplotype. In humans, each HLA allele is named with a number. For instance, for a given individual, his haplotype might be HLA-A2, HLA-B5, HLA-DR3, etc... Each heterozygous individual will have two MHC haplotypes, one in each chromosome (one of paternal origin and the other of maternal origin).

The MHC genes are highly polymorphic; this means that there are many different alleles in the different individuals inside a population. The polymorphism is so high that in a mixed population (non-endogamic) there are not two individuals with exactly the same set of MHC genes and molecules, with the exception of the identical twins.

The polymorphic regions in each allele are located in the region for peptide contact, which is going to be displayed to the lymphocyte. For this reason, the contact region for each allele of MHC molecule is highly variable, as the polymorphic residues of the MHC will create specific clefts in which only certain types of residues of the peptide can enter. This imposes a very specific link between the MHC molecule and the peptide, and it implies that each MHC variant will be able to bind specifically only those peptides which are able to properly enter in the cleft of the MHC molecule, which is variable for each allele. In this way, the MHC molecules have a broad specificity, because they can bind many, but not all types of possible peptides. This is an essential characteristic of MHC molecules: in a given individual, it is enough to have a few different molecules to be able to display a high variety of peptides.

On the other hand, inside a population, the presence of many different alleles ensures that it will always be an individual with a specific MHC molecule able to load the correct peptide to recognize a specific microbe. The evolution of the MHC polymorphism ensures that a population will not sucumb face to a new pathogen or a mutated one, because at least some individuals will be able to develop an adecuate immune response to win over the pathogen. The variations in the MHC molecules (responsibles for the polymorphism) are the result of the inheritance of different MHC molecules, and they are not induced by recombination, as it is the case for the antigen receptors.

Because of the high levels of allelic diversity found within its genes, MHC has also attracted the attention of many evolutionary biologists.

Molecular biology of MHC proteins

The classical MHC molecules (also referred to as HLA molecules in humans) have a vital role in the complex immunological dialogue that must occur between T cells and other cells of the body. At maturity, MHC molecules are anchored in the cell membrane, where they display short polypeptides to T cells, via the T cell receptors (TCR). The polypeptides may be "self," that is, originating from a protein created by the organism itself, or they may be foreign ("nonself"), originating from bacteria, viruses, pollen, and so on. The overarching design of the MHC-TCR interaction is that T cells should ignore self-peptides while reacting appropriately to the foreign peptides.

The immune system has another and equally important method for identifying an antigen: B cells with their membrane-bound antibodies, also known as B cell receptors (BCR). However, whereas the BCRs of B cells can bind to antigens without much outside help, the TCRs require "presentation" of the antigen through the help of MHC. For most of the time, however, MHC are kept busy presenting self-peptides, which T cells should appropriately ignore. A full-force immune response usually requires the activation of B cells via BCRs and T cells via the MHC-TCR interaction. This duality creates a system of "checks and balances" and underscores the immune system's potential for running amok and causing harm to the body (see autoimmune disorders).

MHC molecules retrieve polypeptides from the interior of the cell they are part of and display them on the cell's surface for recognition by T cells. However, MHC class I and MHC class II differ significantly in the method of peptide presentation.

MHC Class-I

In eutheria, the Class-I region contains a group of genes which is conserved between species, in the same order along the region.

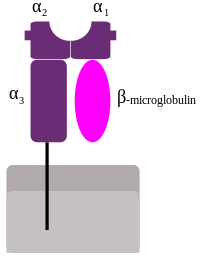

MHC Class-I genes (MHC-I) code glucoproteins, with immunoglobulin structure: they present one heavy chain type α, subdivided in three regions: α1, α2 y α3. These three regions are exposed to the extracellular space, and they are linked to the cellular membrane through a transmembrane region. The α chain is always asociated to a molecule of β2 microglobulin, which is coded by an independent region on chromosome 15. These molecules are present in the surface of all nucleated cells.[6]

The most important function of the gene products for the Class-I genes is the presentation of intracellular antigenic peptides to the cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8+). The antigenic peptide is located in a cleft existing between the α1 and α2 regions in the heavy chain.

In humans, there are many different isotypes (different genes) for the Class-I molecules, which can be grouped as:

- "classic molecules", whose function consist in antigen presentation to the T8 lymphocytes: inside this group we find HLA-A, HLA-B y HLA-C.

- "non classic molecules" (named also MHC class IB), with specialized functions: they do not present antigens to T lymphocytes, but they interact with inhibitory receptors in NK cells; inside this group we find HLA-E, HLA-F, HLA-G.

MHC Class-II

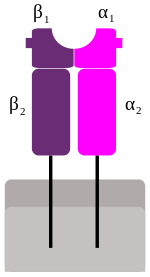

These genes code glucoproteins with immunoglobulin structure, but in this case the functional complex is formed by two chains, one α and one β (each one with two domains: α1 and α2, β1 and β2). Each chain is linked to the cellular membrane through a transmembrane region, and both chains are confronted, with domains 1 and 2 consecutives, in the extracellular espace.[6]

These molecules are present mostly in the membrane of the antigen presenting cells (dendritic and phagocytic cells), where they present processed extracellular antigenic peptides to the helper T lymphocytes (CD4+). The antigenic peptide is located in a cleft formed by α1 and β1 peptides.

MHC-II molecules in humans present 5-6 isotypes, and can be grouped in:

- "classic molecules", presenting peptides to T4 lymphocytes; inside this group we find HLA-DP, HLA-DQ, HLA-DR;

- "non classic molecules", accesories, with intracellular functions (they are not exposed in the cellular membrane, but in internal membrares in lysosomes); normally, they load the antigenic peptides on the classic MHC-II molecules; in this group are included HLA-DM and HLA-DO.

On top of the MHC-II molecules, in the Class-II region are located genes coding for antigen processing molecules, such as TAP (transporter associated with antigen processing) or Tapasin.

MHC Class-III

This class include genes coding several secreted proteins with immune functions: components of the complement system (such as C2, C4 and B factor) and molecules related with inflammation (cytokines such as TNF-α, LTA, LTB) or heat shock proteins (hsp).

Class-III molecules do not share the same function as class- I and II molecules, but they are located between them in the short arm of human chromosome 6, and for this reason they are frequently described together.

Functions of MHC-I and II molecules

Both types of molecules present antigenic peptides to T lymphocytes, which are responsible for the specific immune response to destroy the pathogen producing those antigens. However, Class-I and II molecules correspond to two different pathways of antigen processing, and are associated to two different systems of immune defense:[6]

| Characteristic | MHC-II pathway | MHC-I pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Composition of the stable peptide-MHC complex | Polymorphic chains α and β, peptide binds to both | Polymorphic chain α and β2 microglobulin, peptide bound to α chain |

| Types of antigen presenting cells (APC) | Dendritic cells, mononuclear phagocytes, B lymphocytes, some endothelial cells, epithelium of thymus | All nucleated cells |

| T lymphocytes able to respond | Helper T lymphocytes (CD4+) | Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CD8+) |

| Origin of antigenic proteins | Proteins present in endosomes or lysosomes (mostly internalized from extracellular medium) | cytosolic proteins (mostly synthetized by the cell; may also enter from the extracellular medium via phagosomes) |

| Enzymes responsible for peptide generation | Proteases from endosomes and lysosomes (for instance, cathepsin) | Cytosolic proteasome |

| Location of loading the peptide on the MHC molecule | Specialized vesicular compartment | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| Molecules implicated in transporting the peptides and loading them on the MHC molecules | DM, invariant chain | TAP (transporter associated with antigen processing) |

T lymphocytes belonging to one specific individual present a property called MHC restriction (see below): they only can detect an antigen if it is displayed by an MHC molecule from the same individual. This is due to the fact that each T lymphocyte has a dual specificity: the T cell receptor (TCR) recognizes at the same time some residues from the peptide and some residues from the displaying MHC molecule. This property is of great importance in organ transplantation, and it implies that, during their development, T lymphocytes must "learn" to recognize the MHC molecules belonging to the individual (the "self" recognition), during the complex process of maturation and selection having place in the thymus.

MHC molecules can only display peptides. For this reason, as T lymphocytes can only recognize an antigen if it is displayed by an MHC molecule, they only can react to antigens of proteic origin (coming from microbes) and not to other types of chemical compounds (neither lipids, nor nucleic acids, nor sugars). Each MHC molecule can display only one peptide each time, because the cleft in the molecule has space only to load one peptide. However, one given MHC molecule has a broad specificity, because it can display many different peptides (although not all).

MHC molecules obtain the peptide that they display to the outside of the cell during their own biosynthesis, inside the cell. That means that those peptides come from microbes that are inside the cell. This is the reason why T lymphocytes, which only can recognize a peptide if it is displayed by an MHC molecule, are only able to detect microbes associated to cells, developing only an immune response against intracellular microbes.

It is important to notice that MHC-I molecules acquire peptides coming from cytosolic proteins, whereas MHC-II molecules acquire peptides from proteins contained in intracellular vesicles. For this reason, MHC-I molecules display "self" peptides, viral peptides (synthesized by the own cell) or peptides coming from ingested microbes in phagosomes. MHC-II molecules, however, display peptides coming from microbes ingested in vesicles (MHC-II molecules are present only in cells with phagocytic capacity). MHC molecules are stable on the cell membrane only if they display a loaded peptide: the peptide stabilizes the structure of the MHC molecules, whereas "empty" molecules are degraded inside the cell. MHC molecules loaded with a peptide can remain in the cell membrane for days, long enough to ensure that the correct T lymphocyte will recongize the complex and initiate the immune response.

In each individual, MHC molecules can display both foreign peptides (coming from pathogens) as well as peptides coming from the self proteins of this individual. For this reason, in a given moment, only a small fraction of the MHC molecules in one cell will display a foreign peptide: most of the displayed peptides will be self peptides, because these are much more abundant. However, T lymphocytes are able to detect a peptide displayed by only 0.1%-1% of the MHC molecules to initiate an immune response.

On the other hand, the self peptides cannot initiate an immune response (except in the case of autoimmune diseases), because the specific T lymphocytes for the self peptides are destroyed or inactivated in the thymus. However, the presence of self peptides displayed by MHC molecules is essential for the supervising function of the T lymphocytes: these cells are constantly patrolling the organism, verifying the presence of self peptides associated to MHC molecules. In the rare cases in which they detect a foreign peptide, they will initiate an immune response.

Role of MHC molecules in transplants rejection

MHC molecules were identified and named precisely after their role in transplants rejection between mice from different endogamic strains. In humans, MHC molecules are the "human leukocyte antigens" (HLA). It took more than 20 years to understand the physiological role of MHC molecules in peptide presentation to T lymphocytes.[7]

As previously described, each human cell express 6 MHC class-I alleles (one HLA-A, -B and -C allele from each progenitor) and 6-8 MHC class-2 alleles (one HLA-DP and -DQ, and one or two HLA-DR from each progenitor, and some combinations of these). The MHC polymorphism is very high: it is estimated that in the population there are at least 350 alleles for HLA-A genes, 620 alleles for HLA-B, 400 alleles for DR and 90 alleles for DQ. As these alleles can be inherited and expressed in many different combinations, each individual in the population will most likely express some molecules which will be different from the molecules in another individual, except in the case of identical twins. All MHC molecules can be targets for transplant rejection, but HLA-C and HLA-DP molecules show low polymorphism, and most likely they are less important in rejection.

In a tranplant (an organ transplantation or stem cells transplantation), MHC molecules work as antigens: they can initiate an immune response in the receptor, thus provoking the transplant rejection. MHC molecules recognition in cells from another individual is one of the most intense immune responses currently known. The reason why an individual reacts against the MHC molecules from another individual is pretty well understood.

During T lymphocytes maturation in the thymus, these cells are selected according to their TCR capacity to weakly recognize complexes "self peptide:self MHC". For this reason, in principle T lymphocytes should not react against a complex "foreign peptide:foreign MHC", which is what can be found in transplanted cells. However, what seems to happen is a kind of cross-reaction: T lymphocytes from the receptor individual can be mistaken, because the MHC molecule of the donor is similar to self MHC molecule in the binding region to the TCR (the MHC variable region is in the binding motif for the peptide they display). For this reason, the lymphocytes from the receptor individual mistake the complex present in the cells or the transplanted organ as "foreign peptide:self MHC" and they initiate an immune response against the "invading" organ, because this is perceived as if it was an infected or tumoral self organ, but with an extremely high number of complexes able to initiate an immune response. The recognition of the foreign MHC as self by T lymphocytes is called allorecognition.

There can be two types of transplant rejection mediated by MHC molecules (HLA):

- hyperacute rejection: it happens when the receptor individual has preformed anti-HLA antibodies, generated before the trasplantation; this can be due to previous blood transfusions (because this includes donor lymphocytes, expressing HLA molecules), to the generation of anti-HLA during pregnancy (against the HLA molecules from the father present in the fetus) and due to a previous trasplantation;

- acute humoral rejection and chronic disfunction of the transplanted organ: due to the formation of anti-HLA antibodies in the receptor individual, against the HLA molecules present in the endothelial cells of the transplanted tissue.

In both cases, there is an immune reaction against the transplanted organ, which can produce lesions in the organ, eventually producing lost of function, immediately in the first case, and progressive in the second one.

For this reason, it is crucial to realize a cross-reaction test between donor cells and receptor serum, to detect the potential presence of preformed anti-HLA antibodies in the receptor against donor HLA molecules, in order to avoid the hyperacute rejection. Normally, what is checked is the compatibility between HLA-A, -B and -DR molecules: the higher the number of incompatibilities, the lower the 5 years survival of the transplant. Total compatibility exists only between identical twins, but nowadays there are databases of donor information at global level, allowing the optimization of the HLA compatibility between a potential donor and a given receptor.

MHC evolution and allelic diversity

MHC gene families are found in all vertebrates, though the gene composition and genomic arrangement vary widely. Chickens, for instance, have one of the smallest known MHC regions (19 genes), though most mammals have an MHC structure and composition fairly similar to that of humans. Research has determined that gene duplication is responsible for much of the genetic diversity. In humans, the MHC is littered with many pseudogenes.

One of the most striking features of the MHC, in particular in humans, is the astounding allelic diversity found therein, and especially among the nine classical genes. In humans, the most conspicuously-diverse loci, HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DRB1, have roughly 1000, 1600, and 870 known alleles respectively (IMGT/HLA) — diversity truly exceptional in the human genome. The MHC gene is the most polymorphic in the genome. Population surveys of the other classical loci routinely find tens to a hundred alleles — still highly diverse. Many of these alleles are quite ancient: It is often the case that an allele from a particular HLA gene is more closely related to an allele found in chimpanzees than it is to another human allele from the same gene.

In terms of phylogenetics, the marsupial MHC lies between eutherian mammals and the minimal essential MHC of birds, although it is closer in organization to non-mammals. Its Class I genes have amplified within the Class II region, resulting in a unique Class I/II region.[4]

The allelic diversity of MHC genes has created fertile grounds for evolutionary biologists. The most important task for theoreticians is to explain the evolutionary forces that have created and maintained such diversity. Most explanations invoke balancing selection (see polymorphism (biology)), a broad term that identifies any kind of natural selection in which no single allele is absolutely most fit. Frequency-dependent selection and heterozygote advantage are two types of balancing selection that have been suggested to explain MHC allelic diversity. However, recent models suggest that a high number of alleles is not plausibly achievable through heterozygote advantage alone. Pathogenic co-evolution, a counter-hypothesis has recently emerged; it theorizes that the most common alleles will be placed under the greatest pathogenic pressure, thus there will always be a tendency for the least common alleles to be positively selected for. This creates a "moving target" for pathogen evolution. As the pathogenic pressure decreases on the previously common alleles, their concentrations in the population will stabilize, and they will usually not go extinct if the population is large enough, and a large number of alleles will remain in the population as a whole. This explains the high degree of MHC polymorphism found in the population, although an individual can have a maximum of 18 MHC I or II alleles.

MHC and sexual selection

It has been suggested that MHC plays a role in the selection of potential mates, via olfaction. MHC genes make molecules that enable the immune system to recognise invaders; in general, the more diverse the MHC genes of the parents the stronger the immune system of the offspring. It would be beneficial, therefore, to have evolved systems of recognizing individuals with different MHC genes and preferentially selecting them to breed with.

Yamazaki et al. (1976) showed this to be the case for male mice, which show a preference for females of different MHC. Similar results have been obtained with fish.[8]

In 1995, Swiss biologist Claus Wedekind determined MHC-dissimilar mate selection tendencies in humans. In the experiment, a group of female college students smelled t-shirts that had been worn by male students for two nights, without deodorant, cologne, or scented soaps. An overwhelming number of women preferred the odors of men with dissimilar MHCs to their own. However, their preference was reversed if they were taking oral contraceptives.[9] The hypothesis is that MHCs affect mate choice and that oral contraceptives can interfere with this. A study in 2005 on 58 test subjects found that the women were more indecisive when presented with MHCs similar to their own.[10] However, without oral contraceptives, women had no particular preference, contradicting the earlier finding.[11] However, another study in 2002 showed results consistent with Wedekind's—paternally inherited HLA-associated odors influence odor preference and may serve as social cues.[12]

In 2008, Peter Donnelly and colleagues proposed that MHC is related to mating choice in some human populations.

Rates of early pregnancy loss are lower in couples with dissimilar MHC genes.

Restriction

A given T cell is restricted to recognize a peptide antigen only when it is bound to self-MHC molecules.

MHC restriction is particularly important when primary lymphocytes are developing and differentiation in the thymus or bone marrow. It is at this stage that T cells die by apoptosis if they express high affinity for self-antigens presented by an MHC molecule or express too low affinity for self MHC. This is ensured through two distinct developmental stages: positive selection and negative selection.

See also

- Cell-mediated immunity

- Disassortative sexual selection

- Humoral immunity

- Transplant rejection

- Monell Chemical Senses Center, a research facility which works in this field

References

- ↑ Kimball's Biology], Histocompatibility Molecules

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Reece, Jane; Campbell, Neil (2002). Biology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-6624-5. p. 907

- ↑ MHC Sequencing Consortium (1999). "Complete sequence and gene map of a human major histocompatibility complex". Nature 401 (6756): 921–923. doi:10.1038/44853. PMID 10553908.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Belov, Katherine; Janine E. Deakin, Anthony T. Papenfuss, et al. (March 2006). "Reconstructing an Ancestral Mammalian Immune Supercomplex from a Marsupial Major Histocompatibility Complex". PLoS Biol 4(3) (e46): e46. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040046. PMID 16435885. PMC 1351924. http://biology.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10%2E1371%2Fjournal%2Epbio%2E0040046.

- ↑ Aderem, Alan; Underhill, David (April 1999). "Mechanisms of Phagocytosis in Macrophages". Annual Review of Immunology 17: 593–623. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.593. PMID 10358769.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Abbas; Lichtman A.H. (2009). "Ch.3 Antigen capture and presentation to lymphocytes". Basic Immunology. Functions and disorders of the immune system (3rd ed.). p. A.B.. ISBN 978-1-4160-4688-2.

- ↑ Abbas; Lichtman A.H. (2009). "Ch.10 Immune responses against tumors and transplants". Basic Immunology. Functions and disorders of the immune system (3rd ed.). p. A.B.. ISBN 978-1-4160-4688-2.

- ↑ Boehm, T; Zufall, F (2006). "MHC peptides and the sensory evaluation of genotype". Trends Neurosci 29 (2): 100–107. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2005.11.006. PMID 16337283.

- ↑ Wedekind, C; Seebeck, T; Bettens, F; Paepke, A J (June 1995). "MHC-dependent mate preferences in humans". Proc Biol Sci 1359 (260): 245–249. doi:10.1098/rspb.1995.0087. PMID 7630893.

- ↑ Santos, P S; Schinemann, J A; Gabardo, J; Bicalho, Mda G (April 2005). "New evidence that the MHC influences odor perception in humans: a study with 58 Southern Brazilian students". Horm Behav. 47 (4): 384–388. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.005. PMID 15777804.

- ↑ The pill makes women pick bad mates

- ↑ Jacob S, McClintock MK, Zelano B, Ober C (February 2002). "Paternally inherited HLA alleles are associated with women's choice of male odor". Nat. Genet. 30 (2): 175–9. doi:10.1038/ng830. PMID 11799397.

External links

- MeSH Major+Histocompatibility+Complex

- Molecular individuality (German online-book 2009)

- Sexual attraction is linked to MHC compatibility

- NetMHC 3.0 server — predicts binding of peptides to a number of different MHC (HLA) alleles

- T-cell Group - Cardiff University

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||